Battle Creek Offers a Lifeline for Endangered Winter-Run Chinook Salmon

Winter-Run Chinook: A Uniquely Californian Salmon

The Sacramento River is home to four distinct “runs” of Chinook (or king) Salmon. Each run is named for the season in which the adult salmon enter freshwater from the ocean as they make their way upstream to spawn: winter-run, spring-run, fall-run and late-fall run. These four runs mean the Sacramento River is home to the most diverse Chinook salmon populations on Earth. The river is capable of supporting this vast diversity of salmon populations because of the diverse landscape that it flows through.

Fall-run are a rain salmon, spawning in reaches of the rivers along the valley floor when fall and winter storms swell the Sacramento and its tributaries with water. Spring-run are a mountain fish, silver and sleek, entering the river from the ocean just as warm spring temperatures begin to thaw the snowpack off the high peaks of the Sierra Nevada (and to a lesser extent off the Coast Range). Imagine them “reverse-surfing” the pulse of spring snowmelt up into deep, cold mountain canyons where they will spend all summer waiting to spawn once water temperatures decrease in the fall. Late-fall run Chinook behave as a mix between spring and fall-run.

Winter-run evolved with the unique, bountiful, cold groundwater springs that bubble up from the ground year-round to feed the McCloud River, Upper Sacramento River, Pit River, and Battle Creek. These streams originate from the volcanic aquifers of Mount Shasta and Mount Lassen, both of which store water from snowmelt and slowly release it as steady, reliable, cold flow throughout the summer months. Winter-run salmon took advantage of this unique consistent source of ice-cold summer flow in order to spawn between April and early August. Salmon are cold-water fish and the cold flow from volcanic springs allowed salmon eggs and embryos to incubate in the cold water they need during even the hottest of months.

The day the gates closed on Shasta Dam in 1943, the spring-fed headwaters of all three of these rivers (approximately 200 miles of California’s prime salmon and steelhead spawning habitat) disappeared behind a 602-foot-tall wall of cement. Although devastating for all four distinct runs of Central Valley Chinook salmon, the high dam hit the Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon the hardest, because it cut off access to most of this cold summer water, disrupting a salmon life-history strategy that is uniquely Californian.

Vulnerable Populations

Today, winter-run Chinook salmon are listed as an endangered species by both the state and federal governments. Populations over the last 10 years have averaged less than 5,000 fish, down from historical runs of 200,000 spawners per year. Population numbers hit an all-time low abundance in 1994 when, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), an estimated 189 adults returned. From 1967 through the early 1990s, populations declined at an average rate of 18% per year, or roughly 50% per generation. CalTrout’s State of the Salmonid II Report (SOS II) lists Sacramento River winter-run Chinook as highly vulnerable to extinction within the next 50 years.

Extirpated (meaning locally extinct) from their historical mountain spring-fed watersheds, winter-run Chinook salmon clung to a precarious existence in the Sacramento River on the sweltering valley floor near Redding, surviving on cold water released by regulators from Shasta Reservoir and Keswick Dam. This desperate strategy leaves winter-run salmon highly vulnerable to water operations at the end of each summer when the “cold water pool” in Shasta reservoir is at its lowest, especially during drought. For example, CDFW estimated that in the drought of 2014 and 2015 the vast majority of the juvenile Sacramento River winter-run Chinook production was lost after the cold-water pool in Shasta Reservoir was depleted and the Sacramento River exceeded temperature thresholds for egg incubation. It has become clear that this is an untenable situation and that to avoid extinction, something more must be done.

Today, after more than 100 years of habitat degradation and population declines, new opportunities are opening up to reverse negative trends; and CalTrout is ramping up efforts to ensure the future of this species.

Battle Creek: A Restoration Opportunity

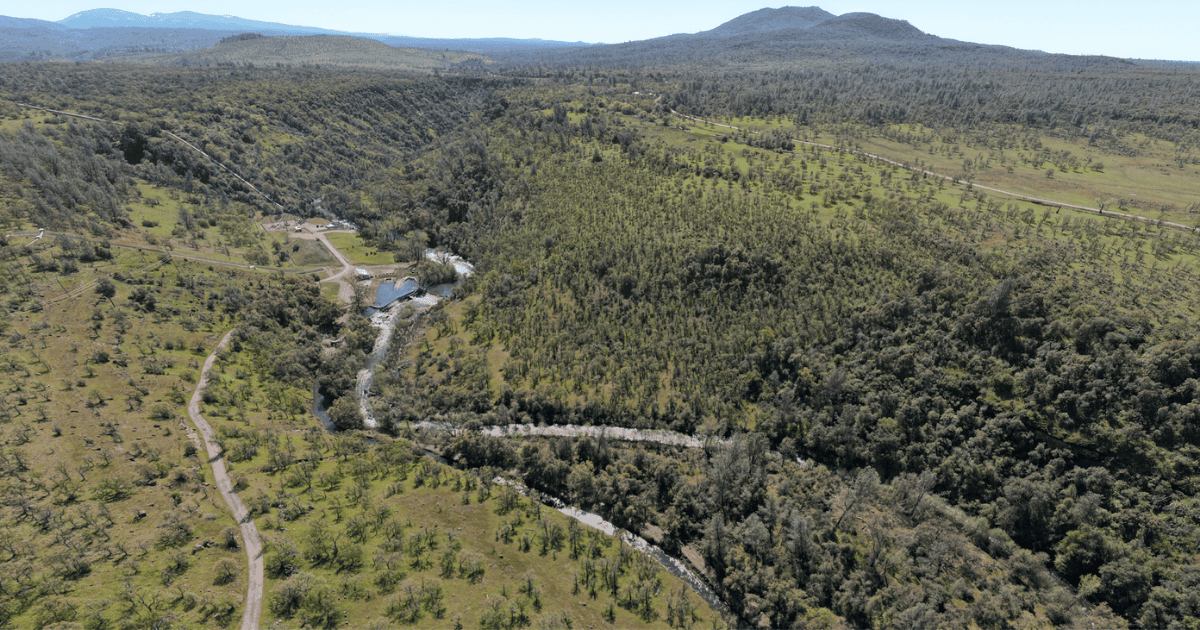

The Battle Creek watershed, located in the heart of California's largest watershed, the Sacramento River, is one of the most important restoration opportunities for winter-run Chinook salmon. Battle Creek offers prime spring-fed, cold-water habitat that could give these fish a lifeline — but much of this critically important spawning habitat is currently locked behind multiple dams while floodplain rearing habitat is degraded by levees and other land use.

In response, CalTrout and our partners have launched several restoration projects in the Battle Creek watershed to reconnect salmon with essential habitats throughout the watershed. These efforts aim to address the entire lifecycle of the salmon—from spawning adults to juvenile rearing and to outmigration. Through a combination of innovative habitat enhancement projects, infrastructure improvements, and strategic partnerships, CalTrout is working to remove barriers and reconnect fish with their upstream migratory routes to headwater spawning habitat, restore floodplains for juvenile rearing, and reactivate the food web in the lower watershed on which healthy young salmon depend.

Winter-Run Chinook Salmon Reintroduction to Battle Creek

In 2016, our state and federal agency partners published the Battle Creek Winter-Run Chinook Salmon Reintroduction Plan which lays out the strategies for recolonization and long-term management of salmon in the watershed. Then, in the spring of 2018, over 200,000 hatchery-raised juvenile winter-run Chinook were released into the watershed, jumpstarting the reintroduction process and amplifying the need to restore habitat.

Removing Barriers to the Headwaters

Reintroduction highlighted the need to accelerate the decommissioning of the Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project owned and operated by Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E). The hydroelectric system includes eight dams in anadromous reaches, two reservoirs, and three forebays located throughout the North and South Forks of the Battle Creek watershed. Originally built to support mining operations in Shasta County, the project blocked winter-run salmon from the only other cold, spring-fed water habitat below Shasta Dam. By removing diversion dams on the South and North Forks of Battle Creek, salmon could be reconnected with approximately 46 miles of historic habitat. These changes would allow migrating adults to access cold-water holding pools and spawning areas, improving their chances of successful reproduction. Additionally, the restoration of these cold-water habitats could help maintain the suitable temperature ranges for both adult and juvenile salmon throughout the year.

PG&E’s license for this project will expire in 2026. In 2024, CalTrout assembled a coalition of resource agencies, NGOs, Tribes, and community members to accelerate dam removal. The coalition works to prevent delays in decommissioning and provide technical resource support for the process. CalTrout is also developing a water temperature model for Battle Creek which will explore how water temperature may change with various decommissioning and climate change scenarios.

Momentum for barrier removal is building. The first dam removal occurred in 2010 with the removal of Wildcat Dam on the North Fork which opened miles of fish habitat. In 2021, CalTrout and our partners completed construction on a rock barrier in Eagle Canyon, resolving the largest fish passage barrier in North Fork Battle Creek and reconnecting eight miles of habitat (watch the video below to learn more). And now, PG&E plans to remove Inskip Diversion Dam this summer!

Restoring Floodplains and the Food Web

Baby fish need food after they emerge from the gravels of the headwaters where their mother had laid her eggs. Floodplain wetlands are food factories for rivers and their denizens. The confluence of Battle Creek and the Sacramento River once represented the largest extent of wetlands available to young salmon in the upper portion of the Sacramento Valley. Most of these floodplain wetlands are no longer accessible to fish after levees were built and marshlands were drained to facilitate agriculture and ranching. The Battle Creek Floodplain Enhancement Project aims to rehabilitate a mosaic of marshes, side channels, riparian forests, and other floodplain habitats to provide a wealth of food resources for young salmon while also improving habitat for waterfowl, shorebirds, and other wildlife.

This last year, working with CDFW, Ducks Unlimited, and River Partners, CalTrout enhanced four acres of wetlands along lower Battle Creek just downstream of Coleman National Fish Hatchery. By restoring water flow through the wetlands and reconnecting the outflow to the creek, the project reconnects the extremely high aquatic productivity found in the floodplain wetlands to Battle Creek’s aquatic food web where this “fish food” is once again accessible to small salmon and trout in Battle Creek. The project re-contoured the wetlands and installed new water control structures, improvements that allowed for a greater volume of floodplain water rich with zooplankton (fish food) to be exported to the creek where it serves as a critical food resource for rearing juvenile salmonids.

In addition to the improved habitat for waterfowl and the abundant zooplankton growth, the team has recently placed floating cages of juvenile Chinook salmon in Battle Creek and in the restored wetland to track the effects of this fish food project on fish growth. Rigorous scientific documentation of the benefits to fish resulting from this project will accelerate the pace that similar projects can be implemented throughout the region.

Expanding Floodplain Restoration Through a String of Pearls

CalTrout’s String of Pearls project aims to improve floodplain and side-channel habitats along the entire migration route that salmon take down the Sacramento River to the ocean. A major component of the project employs the innovative Ecological Floodplain Inundation Potential (EcoFIP) analysis. EcoFIP, developed by our partners at cbec eco-engineering, is a GIS-based tool that allows us to identify and prioritize the very best floodplain restoration opportunities along the entire 300-mile stretch of the Sacramento River from Redding to Rio Vista. The tool helps select the most effective sites for restoration, considering factors such as depth and velocity of flood waters under specific flow scenarios, habitat connectivity, flood protection benefits, groundwater recharge potential, and socio-economic metrics. These floodplain projects integrate ecological goals with community resilience, offering job opportunities, recreational benefits, flood-risk reduction, and improved groundwater management and putting us a major step closer to restoring thriving Battle Creek and Sacramento River salmon runs.

Looking Ahead: A Vision for Resilient Salmon Populations

Restoration of the Battle Creek watershed represents a forward-thinking approach to salmon restoration—one that acknowledges the challenges posed by climate change, water management, and habitat loss, while also focusing on innovative solutions that will benefit both wildlife and local communities. As Battle Creek’s ecosystem continues to improve, so too does its potential to support thriving populations of Chinook salmon.

CalTrout is on a mission to protect winter-run Chinook salmon, and our network of projects in Battle Creek will help restore vital links in the salmon life cycle, ensuring that future generations of these iconic fish will have the resources they need to survive and thrive in a rapidly changing world. With continued efforts and growing partnerships, Battle Creek holds the promise of a healthier, more sustainable future for both people and fish.